Product-category. A good level to understand a company's strategy is to consider the product-category level. A product category includes the individual products that fulfil a similar need for the buyers. The definition of a product category is often straightforward, but not always. Here are a few examples of product categories:

- Carbonated sweet softdrinks. In the US market this is a distinct product category, even though the definition has become somewhat blurred due to the popularity of non-carbonated softdrinks as well as bottled water. In the Asian context the definition also needs to deal with tea-based drinks.

- Packaging containers for beverages. This would include aluminium, glass, plastic and waxed paper. However, it could be argued that each raw-material should be a separate product-category.

- Commuter transportation. This would include metropolitan rail as well as bus services in large cities.

- Smartphones. Since a smartphone is able to function like a computer it should be seen as a different product category compared to the traditional mobile phone.

The product category often corresponds to a business-unit inside a company. However, there is no guarantee that there will be a direct correspondence. If a company has more than one business-unit for a particular product-category we should consider the different business-units separately. And if a business-unit includes several product-categories we should consider the different product-categories separately.

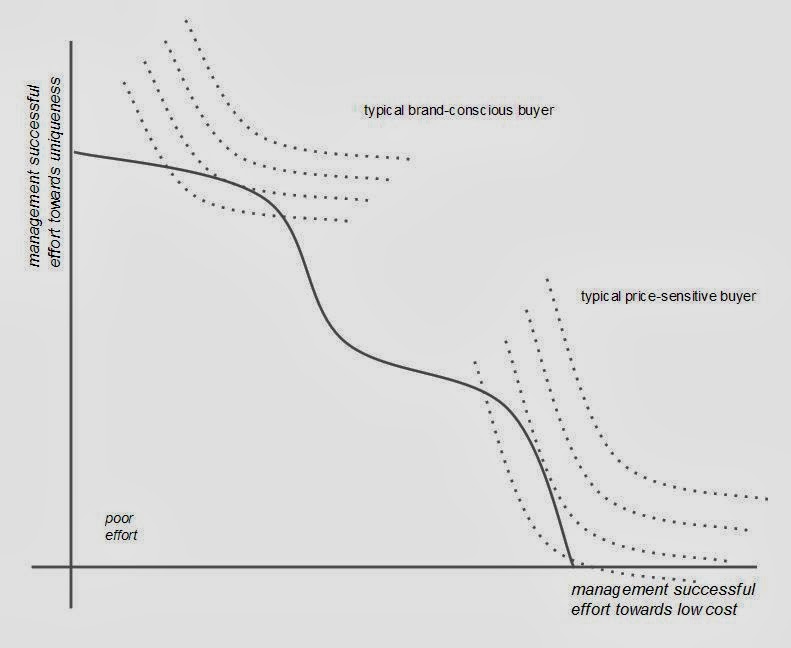

Generic strategies. Generally, there are two ways for a company to earn a profit. These two ways translates into two strategies (see figure 1):

- Make the products different so that you can charge a higher price. I will refer to this as uniqueness.

- Make the products cheaper to manufacture and sell. I will refer to this as low cost.

|

| Figure 1. |

Strategy possibility frontier. The frontier represents the limit of the possible at given point in time. A few points regarding the shape of the frontier should be highlighted:

- At the frontier there is always a trade-off between being unique and being low cost. It costs money to be unique (e.g. advertising, product development, customer service), which mean that you need to forego a low cost position to stand the chance of gaining increased revenue for being perceived as more unique. And if you target a low-cost position, you simply do not have the money to be unique.

- At the endpoints it is possible to gain a large benefit by focusing a little bit on the other aspect. In other words, there is a benefit for a low-cost company in spending some effort on uniqueness. Correspondingly, there is a benefit for the unique company to spend some effort managing its costs.

- However, if the company's management effort is similarly devoted to uniqueness and low cost, coordination problems will begin to occur. Practically speaking, it is almost impossible for an organisation to optimally decide on effort, unless one of the two approaches have priority. (An exception is the niche strategy that will be discussed in a later posting.)

So far the framework is conceptual, i.e. we do not know the exact shape of the frontier. However, the frontier is nevertheless real. In a later posting I will explore changes in the shape and location of the frontier over time.

Buyer needs. Different strategic positionings appeal to the buyers to various degree. This is illustrated with indifference curve (see figure 2). Buyers prefer a higher indifference curve. In other words, a company that has a strategy on the frontier will typically be preferred by customers. Each individual customer has his own set of indifference curves indicating that customer's trade-off between uniqueness and price. The indifference curves of two buyers are presented in figure 2.

A feature of many modern product categories is a bifurcation of indifference curves. One segment of the market is more concerned with uniqueness and the other with price. This feature is prevalent when the buyer is a consumer compared to a company. Michael Porter coined the term stuck in the middle for companies that did not follow one of the two strategies. These companies struggle with complex internal management decisions as well as a market that often does not value the resulting products.

The strategy possibility frontier is one way to understand the broad generic strategies in the product-category. Further analysis using the who-what-how model is needed to understand each company's strategy. Strategies that are found away from the stuck-in-the middle area are generally internally consistent. However, internally consistent strategies also need to pass the test of external consistency. More about that in a future posting.

All competitors in a product-category can be plotted in the diagram. This will be the focus of the next couple of postings.

No comments:

Post a Comment