Sweden has two elections this year, one for the European Parliament and one for the Swedish Parliament. I am going to write a bit about Swedish politics from time to time on this blog. I came across the site Political Compass, which uses a modified version of what is normally called the Nolan chart; consider it the standard map to describe political parties.

The model has two axes. The horizontal axis concerns economic values and moves from left to right. The vertical axis concerns social values and moves from libertarian to authoritarian. It should be noted that the model is a simplification or rather a codification of what has been important in the Western political context during the last 50 years. The model does for instance not deal with new issues like the environment, immigration, and globalisation. Furthermore, the scoring in the model is skewed to the libertarian-left. Thus it is better to look at relative differences in the chart.

Using the website, I used my personal knowledge of the political environment in Sweden and filled in a survey to find out the position of each political party in the Swedish parliament. Since I have a fair understanding of Swedish politics, I am pretty happy with this approach, but naturally it can be improved. Figure 1 shows the political environment in Sweden in 1985. At that time there were five parties with representation in the parliament. At that time analysts only referred to the horizontal axis and a key distinction was made between the non-socialist block and the socialist block. Here is a short characterisation:

- Moderaterna. A traditional right-wing party. 21% of votes

- Folkpartiet. A fairly right-wing party, but less conservative socially. 14%

- Centerpartiet. A traditional agrarian party with a strong focus on the environment. 12%

- Socialdemokraterna. A traditional social democratic party. 45%

- Vansterpartiet. A traditional communist party. 5%

At the time, the parties were clearly positioned on the map (i.e. large differences). Many people were loyal to the party their parent had voted for when they grew up. It could be relied upon that Moderaterna would argue for lower taxes, more orderly schools, and harder punishment for criminals. Likewise, Vansterpartiet would take absolutely the opposite standpoint. The world was so simple during the Cold War!

|

| Figure 1. Political parties in the Swedish Parliament in 1985. |

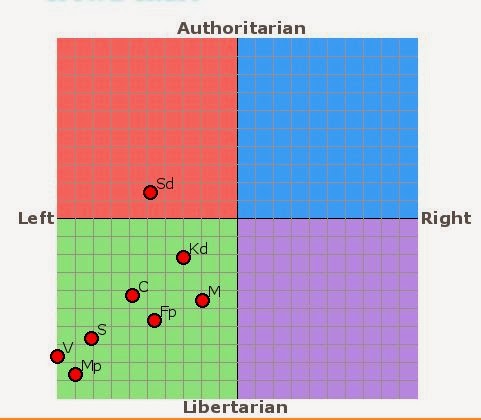

Figure 2 shows the current situation. Let me start by describing the parties, of which there are now eight. The first four parties have been in a coalition government during the last eight years.

- Moderaterna. 30%.

- Kristdemokraterna. A party with traditional Christian roots. Only somewhat loosely modelled after the continental Christian-Democratic parties. 6%

- Folkpartiet. 7%.

- Centerpartiet. 7%.

- Sverigedemokraterna. A nationalist party. Loosely modelled after the west European nationalist parties. 6%.

- Socialdemokraterna. 31%.

- Miljopartiet. A party focused the the environment. Modelled after the continental Green parties. 7%

- Vansterpartiet. 6%

The most interesting change in Swedish politics is the move towards a more libertarian-left point of view; naturally driven by the values of the voters. The right wing party, Moderaterna, has moved the furtherest from its conservative roots, but all parties have made a similar move. The move has been both towards the left (e.g. higher taxes) and more socially inclusive (e.g. gay rights, immigration). Two of the three new parties are also occupying the same space in the figure. The repositioning meant that Socialdemokraterna lost the elections in 2006 and 2010.

Moderaterna's move was almost single-handedly engineered by party-leader, Fredrik Reinfelt, who has been prime minister since the 2006 election. However, the move has made it difficult for his three coalition partners, which are now struggling. Centerpartiet and Kristdemokraterna are especially vulnerable since they only reach 2-5% in the opinion polls. There is no representation in parliament for political parties below 4% of votes. It is unlikely for four non-socialist parties to survive given their current positioning.

The nationalist party, Sverigedemokraterna, has positioned themselves differently. They are now the most authoritarian party, so they take votes from Moderaterna, but they also share some (but not all) traditional left-wing values, so they have also taken votes from Socialdemokraterna. The other seven parties have joined forces and consider Sverigedemokraterna's view on immigration totally unacceptable. This makes it difficult for any of the parties to reposition themselves and opens up for Sverigedemokraterna to do well in the upcoming elections.

|

| Figure 2. Political parties in the Swedish Parliament in 2013. |

Repositioning a political party is a trade-off between gaining new voters and not losing too many of your old voters. It normally takes time for old voters to clearly notice the repositioning. Vansterpartiet used to be a male dominated communist party, but now they are styling themselves as a left-wing feminist party. Their repositioning has been very successful and they have been able to shed most associations with communism. The old communists might find the new party strange, but they will continue to vote for them. The repositioning of Centerpartiet has been less successful. Its rural voters have begun to leave the party and there are just too few urban voters that find its politics tasteful (or are even aware of the new positioning).

I wonder if there is room for a new right-wing party in Sweden. Despite having one of the world's highest tax rates, there is no political party that would like to reduce taxation left. In any case, this will have to wait until after the autumn election. The non-socialist block is likely to lose the election (see here) so arguing for lower taxes is not going to win new votes. However, I suspect there is a lot of dissatisfaction within Moderaterna due to their massive repositioning during the last ten years. There will probably be a backlash against the partly leader and another repositioning of the party somewhat more to the right, unless Mr Reinfelt manages to win the election a third time.

I wonder if there is room for a new right-wing party in Sweden. Despite having one of the world's highest tax rates, there is no political party that would like to reduce taxation left. In any case, this will have to wait until after the autumn election. The non-socialist block is likely to lose the election (see here) so arguing for lower taxes is not going to win new votes. However, I suspect there is a lot of dissatisfaction within Moderaterna due to their massive repositioning during the last ten years. There will probably be a backlash against the partly leader and another repositioning of the party somewhat more to the right, unless Mr Reinfelt manages to win the election a third time.

Finally, a short comparison with Singapore. Here is my subjective assessment of the two parties in the Singaporean parliament. Singapore politics is more authoritarian (e.g. tougher on crime, more order in the schools, religion more important, immigration controlled) than Swedish politics. PAP is also more right-wing than Moderaterna (e.g. lower taxes, free trade agreements).

|

| Figure 3. Political parties in the Singaporean Parliament 2013. |

No comments:

Post a Comment